Effective Ways to Promote The Transfer of Learning

Tyler’s classroom teacher shows you his latest writing assignment. He scored 100% on his latest posttest on structured literacy concepts, but his writing sample is full of errors. Despite all the practice on the k/ck spelling rule, he has not applied it here even once.

You pop into Camryn’s classroom during reading time and despite reading decodable text, she is guessing rather than decoding words.

Mrs. Smith sends Jacob with an assignment hoping you will help him redo it. When you remind Jacob to use the COPS strategy, he looks at you with a perplexed look. “That’s something I do here, not in Mrs. Smith’s room.”

Do any of these situations sound familiar? Are you ever frustrated when you know what a student is capable of, but they aren’t showing that capability in their classroom? These are situations that require effective transfer of learning.

What is the Transfer of Learning?

Transferring is the ability to take skills or strategies learned in an intervention and apply them in the classroom. Transferring learning in a different setting or situation is an important step on the journey to becoming an independent capable reader and writer. It requires a high degree of confidence and skill with a particular concept or strategy and the ability to initiate its use independently.

Why Students Struggle With the Transfer of Learning

Download and print our transfer of learning checklist!

There are several factors that can cause your students to struggle with transferring their learning to their regular education classroom. Some of these are very much student-dependent, some are in the domain of the intervention teacher, and still others are related to the classroom setting.

1. Poor working memory

When a student has a poor working memory, utilizing their strategies independently may stress their cognitive load.

You can think of cognitive load as similar to your ability to carry in groceries from your car. Depending on how efficiently the groceries are packed, how heavy they are, your degree of practice, and your levels of fatigue, how many trips it takes you to carry in a carful of shopping differs. A student’s cognitive load is dependent on their working memory, the difficulty of the task, and their familiarity with the strategies.

For a student with working memory struggles, juggling their strategies may be the equivalent of trying to carry in 3 gallons of milk and a big bag of kitty litter in a paper bag in the rain. Just as you are likely to drop something in that situation, the student is unlikely to have the cognitive bandwidth to manage new tasks independently right away under these circumstances.

2. Not enough repetition

Another reason that students may struggle with transferring learning back to the classroom is that perhaps they have not had enough repetition to truly reach mastery. This may especially require spaced review and repetition to ensure full mastery.

3. Lesson pacing

I’m sure we’ve all had the experience of working with a student whose pace makes completing an entire lesson difficult or a student who always seems to finish with lots of time to read the text at the end of the lesson or play a review game.

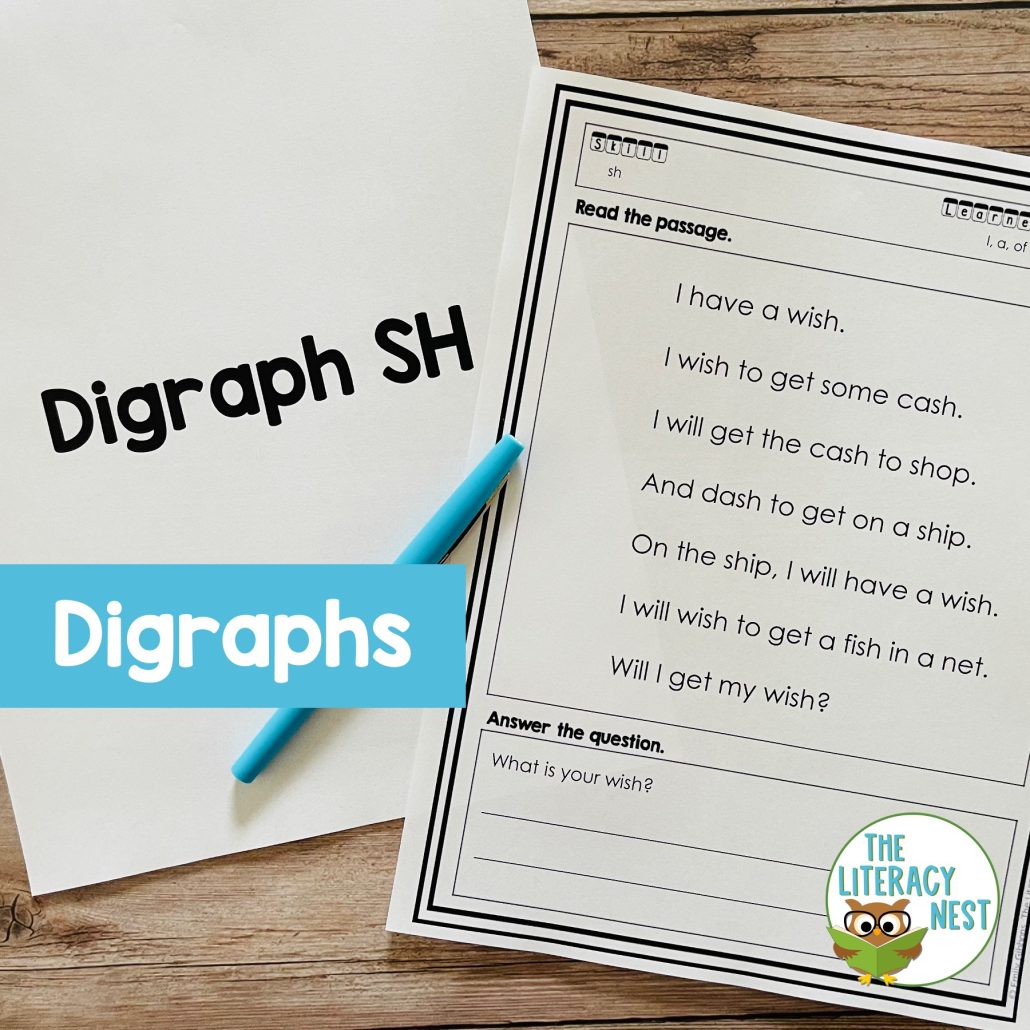

Pacing is a double-edged sword. Pacing that is too slow may reduce opportunities to connect learning from one section of the lesson to the next. Another consequence of poor pacing is not having a good block of time to spend on reading continuous text. The text-reading portion of the lesson is an opportunity for students to transfer learning within the lesson. It is their chance to orchestrate and apply their learning. Pacing that is too fast may not provide adequate thinking time or practice.

4. Skill set may not match student’s reading development

Each student’s reading journey may look different. If the task the student is trying to do in the classroom has skills or elements that they are not yet proficient with, they are likely to struggle. A student who hasn’t yet learned vowel teams is unlikely to utilize them in their spelling correctly.

In a similar way, if we are trying to teach something when a student is missing prerequisite skills, they are unlikely to gain independence. For example, if a student cannot yet blend three sounds, they are going to have a lot of difficulty decoding a book comprised of CVC words.

5. Not enough multisensory teaching

The key to truly making the learning their own is to strengthen the neural pathways through multisensory teaching. If teachers are not using multisensory teaching strategies those connections and pathways are not going to be as strong and flexible as possible.

Learn more about varied practice with decodable text! Watch Varied Practice with Decodable Text.

6. Student needs more time and reinforcement

It is very possible that if these other elements are all in place, the student simply needs more time and reinforcement to transfer their learning to the classroom setting.

7. Ineffective gradual release of responsibility

It is easy for teachers to model and provide a high degree of scaffolding. Likewise, it is relatively easy to allow students to take ownership of learning and stand back. The trickiest part is decreasing the scaffolding gradually being careful not to provide excessive support or to pull the helping hand away too soon.

Learn more about the gradual release of responsibility by listening to season 1, episode 10 of the Together in Literacy podcast: The Gradual Release of Responsibility!

8. Communication with the classroom teacher

It is possible that the classroom teacher needs more clear communication about what the student can do, and what he or she is ready to transfer to the classroom and be given new expectations, checklists, or reminders.

One More Factor:

One more possibility bears mentioning. Suppose a student is receiving structured literacy intervention, but their classroom instruction is based on a balanced literacy model or another model that does not align with the Science of Reading.

In that case, there is likely to be a significant mismatch between the strategies and methods in the classroom and the intervention space. This is necessarily going to slow the transfer of skills and strategies from one setting to another.

How to Encourage the Transfer of Learning for Orton-Gillingham Students:

- Ensure that the Orton-Gillingham lesson matches where the child is in their reading development.

- Monitor the lesson pacing and adjust as needed.

- Remember to be both prescriptive and diagnostic! These are key principles of Orton-Gillingham instruction.

More Important Tips to Keep in Mind:

- Provide enough varied repetition within the lesson, whether it is new material or review. The tips on varied repetition in The Value of Repetition for The Student With Dyslexia will provide even more information for you as you plan the right kind of practice.

- Provide multisensory teaching techniques to strengthen neural pathways. We want to get as many senses working together as possible. Our goal is to use visual, auditory, and kinesthetic or tactile senses simultaneously.

- Weave in review that will strengthen student’s working memory with card games like concentration. Games that utilize both decoding and encoding skills are particularly valuable.

- Communication is key! Keep track of a child’s progress and communicate that to the family and/or the classroom teacher. Let them know when a child has reached mastery of a skill or concept. Let them know when a child knows how to apply specific decoding and encoding strategies and can be reminded to use them. For example: tapping out to spell. This can be done discretely so the student doesn’t feel like other students are noticing them. Another example is using C.O.P.S. or C.U.P.S. when they are checking their work.

- Part of communication is being explicit with students about ways that they can transfer these strategies to their classroom. For example, “You can use C.O.P.S. before you turn in your paper. Sometimes our hands and brains go at different speeds, and you may leave out a word or make another mistake that you will find right away if you do C.O.P.S.” Another example: “If you don’t feel comfortable using your hands to check b and d, you can use the d in your last name on your name tag to check your b’s and d’s.”

- Effective gradual release of responsibility. This is not instant pudding. Effective gradual release of responsibility takes lots of practice, lots of observation, and periodic readjustment. It is never too late to increase or decrease the level of support in response to how students are responding. Remember the old saying: I do it. We do it. You do it.

Remember…

Above all else, it is important to remember that the transfer of knowledge does not happen overnight! It is a process that takes time, a well-trained structured literacy interventionist or specialist, and careful and thoughtful instruction. By using the gradual release of responsibility and the principles of Orton-Gillingham, you can create the steps to help your students get there.

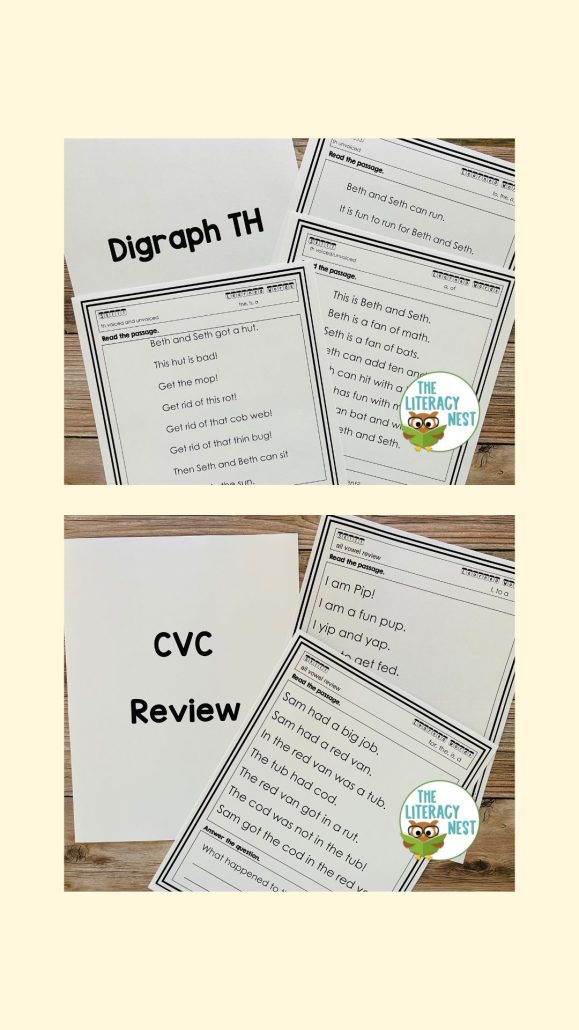

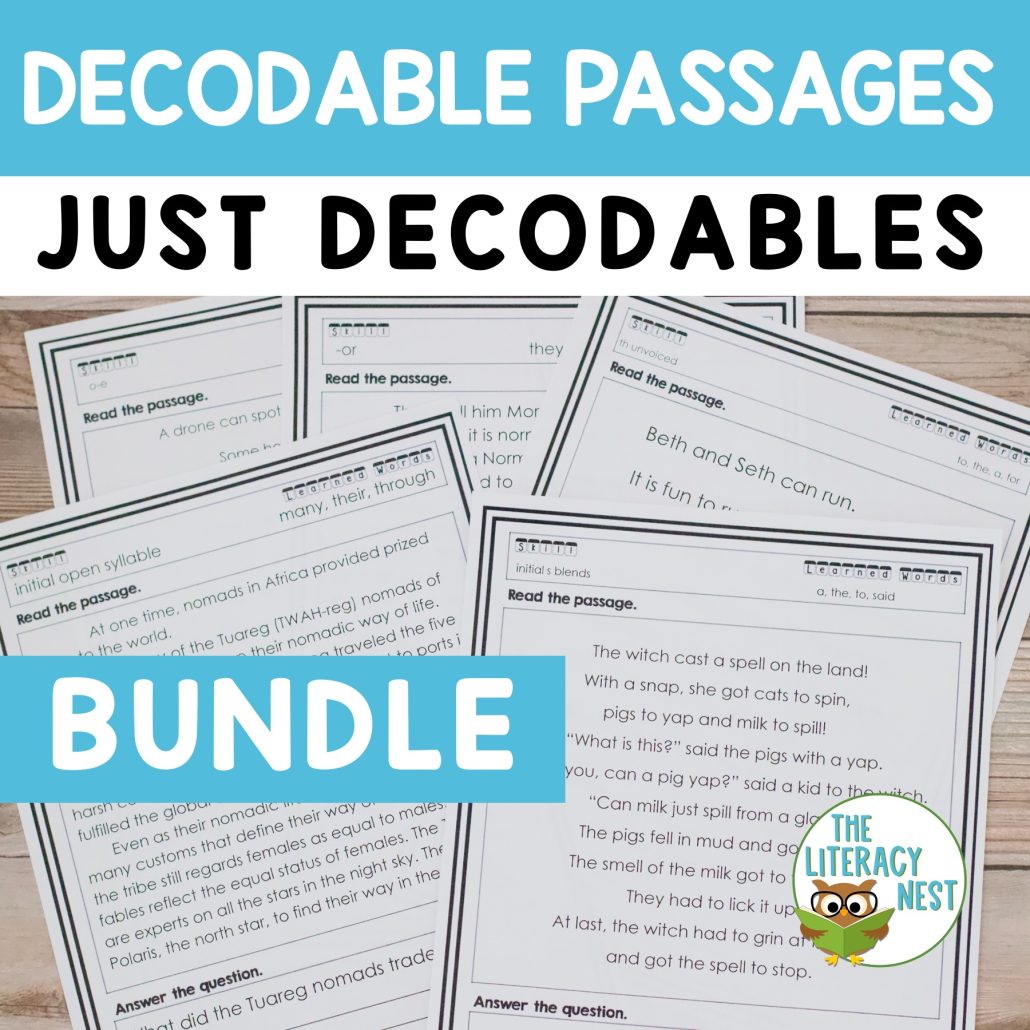

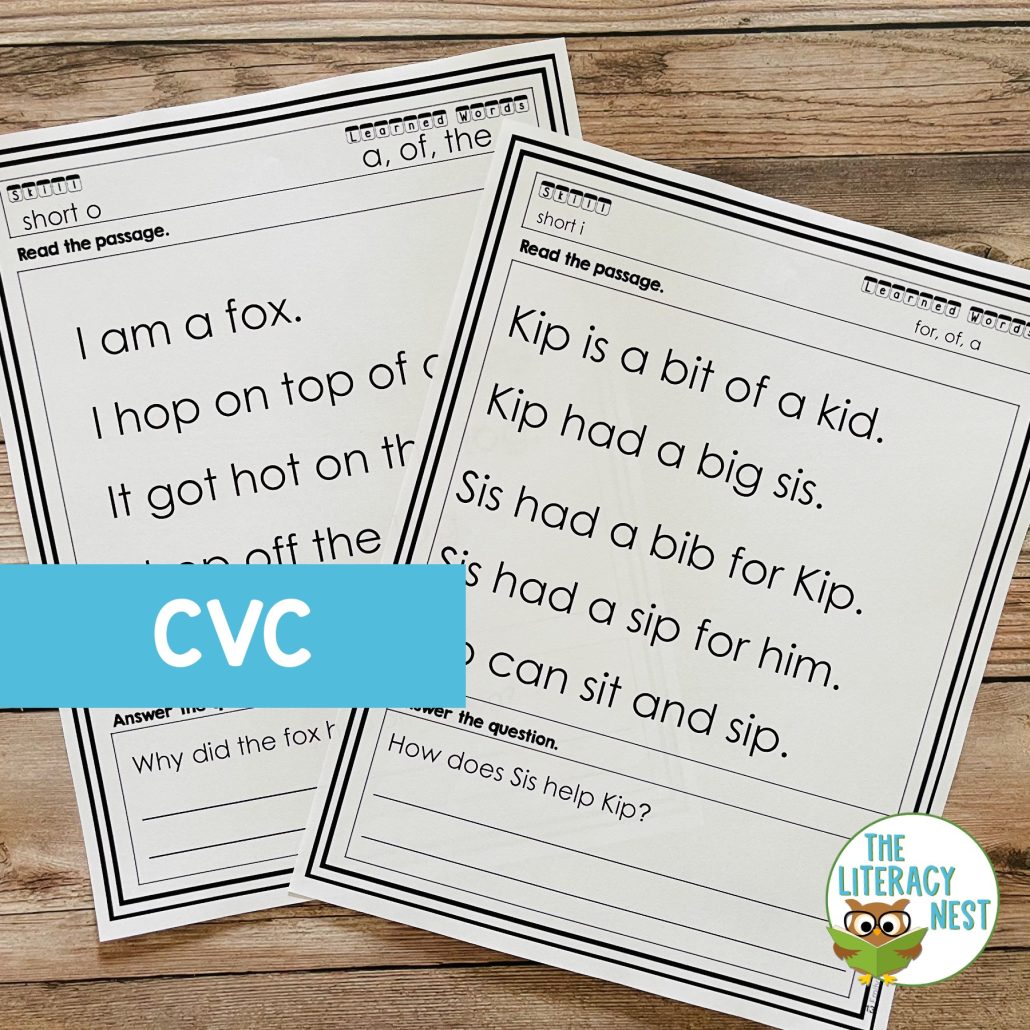

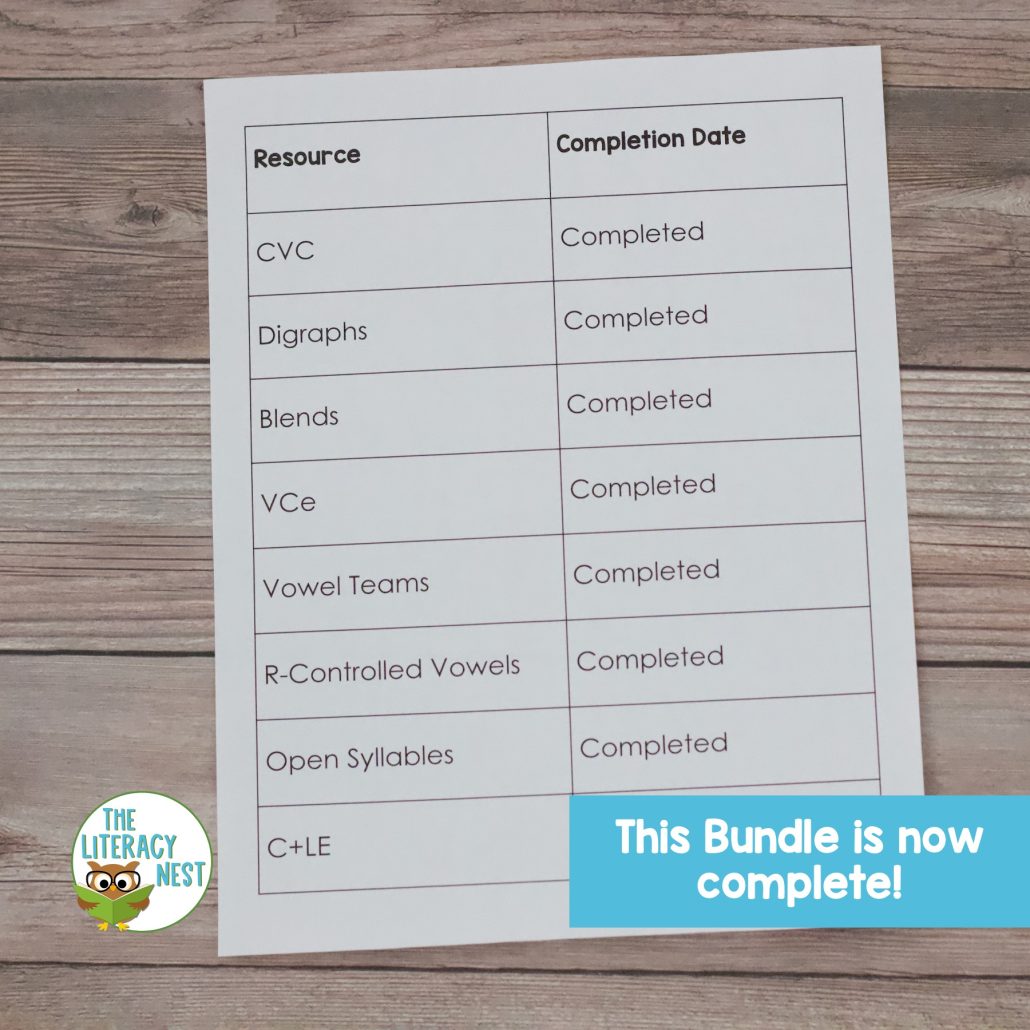

Orton-Gillingham Decodable Readers Bundle

Do your students need decoding practice with specific phonics skills? This bundle of Decodable Phonics Passages was written to help your students learn how to decode with confidence. Your beginning readers will love practicing their decoding and phonics skills with these short decodable passages!

You can grab it in The Literacy Nest Shop or on TpT.

Are you looking for professional development that will help you better support your students? The Literacy Nest has a membership for that…

Building Readers for Life Academy is a monthly membership program that empowers educators AND families. It dives into structured literacy and strategies for ALL learners. With BRFL Academy, you’ll learn what it takes to help EVERY student become a reader for life.